This post is also available in:

עברית (Hebrew)

עברית (Hebrew)

A research team at Texas A&M University has developed the world’s first metallic gel — a new class of material that combines the strength of metals with the flexibility of gels. This breakthrough could lead to safer, high-temperature energy storage and propulsion systems suitable for use in environments where conventional materials fail.

The metallic gel is unlike traditional gels, which are typically made from organic compounds. Instead, it is composed entirely of metals. The process begins by mixing two metal powders and heating them until one melts while the other remains solid. The unmelted metal forms a fine, porous framework that holds the molten metal within, resulting in a structure that appears solid but behaves like a gel.

According to Interesting Engineering, this process occurs only at very high temperatures — often around 1,000°C, depending on the metals used. During heating, the solid component forms a fine structure that holds the molten metal in place, preventing it from collapsing into a liquid pool. According to the researchers, such stability has not been observed before in materials containing liquid metal.

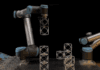

One promising application lies in liquid metal batteries (LMBs), which use molten layers to store and release energy. LMBs are known for their durability and ability to handle large energy loads, but their liquid interiors can shift when moved, leading to short circuits. The metallic gel’s solid framework could prevent that movement, enabling LMBs to function safely in mobile systems such as ships, heavy industrial equipment, or high-temperature vehicles.

To explore this potential, the team constructed a small prototype battery using gel-like electrodes composed of liquid calcium and solid iron for the anode, and liquid bismuth and iron for the cathode. The device successfully generated electricity, and the metallic gel maintained its integrity throughout the process.

The discovery emerged unexpectedly during experiments on metal composites. When the researchers tested a mixture of tantalum and copper, they found that the molten copper did not collapse as anticipated but was supported by a tantalum skeleton. Further testing confirmed that this gel-like state persisted with other metal combinations as well.

Looking ahead, the team believes metallic gels could also stabilize molten salts and even play a role in high-temperature propulsion systems, including those designed for hypersonic vehicles.