This post is also available in:

עברית (Hebrew)

עברית (Hebrew)

Microrobots — machines smaller than a grain of sand — hold enormous promise for tasks that require precision at scales where conventional tools cannot operate. From targeted drug delivery to micro-assembly, these devices could eventually perform work inside the human body or in environments too delicate or hazardous for larger systems. But their size also creates a major design barrier: they are simply too small to carry the sensors, processors, and actuators needed for conventional navigation.

To date, engineers have relied on two main strategies to steer microrobots. One uses external feedback from systems such as optical tweezers or magnetic fields to track individual robots and adjust their paths in real time. While highly accurate, this approach becomes difficult to scale when dealing with large numbers of independently moving robots. The second method, known as reactive control, is more scalable but limited. Here, robots respond immediately to global stimuli, such as light or chemical gradients, but can only perform basic behaviors such as simple taxis or dispersion. Complex maneuvers, coordinated navigation, or movement through structured environments remain out of reach.

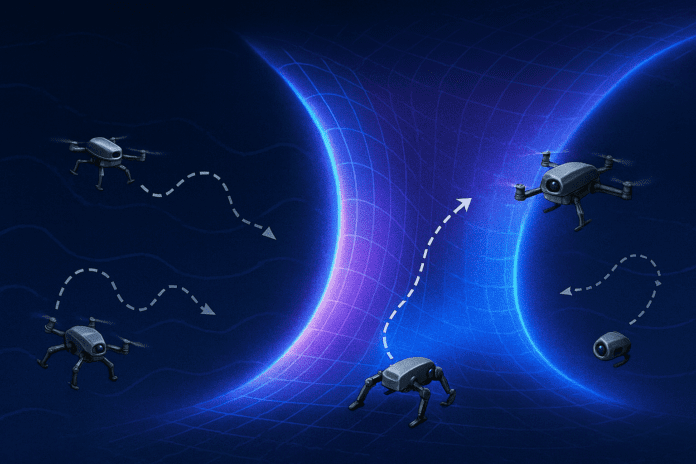

Researchers have now proposed a surprising solution grounded in the mathematics of general relativity. The team discovered that the motion of microrobots under reactive control can be described in the same way physicists describe the trajectory of light moving through curved spacetime. By defining “artificial spacetimes” that reshape the robots’ environment mathematically, the team can map complicated spaces into simpler virtual ones, design the desired paths, and then map the results back to the real environment.

According to TechXplore, this framework allows the robots to perform tasks previously considered impossible for systems with almost no onboard intelligence. Using artificial spacetimes, the researchers demonstrated collision-free navigation near boundaries, patrolling patterns, controlled turning, and convergence on target locations — all without adding any computation or sensing to the robots themselves. Experiments used silicon microrobots powered by projected light fields, with motion controlled entirely by the geometry of the applied “spacetime.”

The approach could also have defense and homeland security uses. Swarms of simple microrobots able to navigate reliably without onboard electronics could support environmental sensing, contamination mapping, or inspection tasks in confined or hazardous settings where larger platforms cannot operate.

Looking ahead, the researchers see potential extensions into time-varying metrics, richer swarm behaviors, and alternative robot designs. If successful, the method could unlock a new generation of microrobotic systems capable of operating collectively and autonomously in environments once thought too complex for machines at this scale.

The research was published here.