This post is also available in:

עברית (Hebrew)

עברית (Hebrew)

Robots are often expected to operate where wheels fail: collapsed buildings, uneven ground, mud, ice, or debris-covered floors. Yet most legged robots still struggle when conditions change suddenly. Traditional control systems rely on carefully tuned physical models and predefined walking patterns, which work well on predictable surfaces but break down when friction drops or terrain becomes irregular. This limitation has slowed the real-world deployment of legged robots in demanding environments.

A new study points to a different approach. Researchers have shown that a quadruped robot can learn to walk across rough and slippery terrain without any human-designed gait or manual tuning. Instead of programming how the robot should move, the system uses deep reinforcement learning to discover stable and efficient locomotion entirely through simulation.

According to Interesting Engineering, the key to making this work is how the robot is trained. Rather than exposing it to complex terrain from the outset, the researchers used a structured learning curriculum. Training begins on flat ground, then gradually introduces slopes, rough surfaces, low-friction areas, and finally mixed environments with added sensor noise. This step-by-step progression allows the robot to build robust movement skills that carry over to unfamiliar conditions.

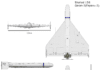

The robot itself is modeled with 12 degrees of freedom and controlled through a hierarchical system. A high-level neural network runs at a slower rate, generating target joint movements, while a low-level controller executes those commands at higher frequency to maintain stability. To understand its environment, the robot relies on both internal sensing—such as joint angles and body orientation—and simulated vision. A depth camera provides local terrain height, slope, and friction estimates.

Training is guided by a reward function that balances multiple objectives: forward speed, balance, smooth motion, low energy consumption, and minimal foot slippage. This encourages natural walking behavior rather than stiff or inefficient movement. Over time, the robot develops strategies that were never explicitly programmed, such as shortening its stride on slippery ground or shifting weight sideways on slopes.

In testing, the trained controller performed reliably across a range of terrains, achieving steady forward speeds with low energy use and relatively low fall rates. Crucially, it also generalized well to new simulation environments it had never seen before.

Legged robots capable of navigating unstable terrain could support disaster response, search and rescue, reconnaissance, and infrastructure inspection in areas too dangerous for humans or wheeled vehicles. The ability to learn robust movement without detailed hand-tuning also shortens development cycles for new robotic platforms.

Challenges remain in transferring these results from simulation to physical hardware, where sensors are noisy and environments less predictable. Still, the study demonstrates that complex, instinct-like movement can emerge from learning alone. That brings autonomous legged robots a step closer to operating reliably in the real world, where conditions are rarely ideal.

The research was published here.