This post is also available in:

עברית (Hebrew)

עברית (Hebrew)

Modern navigation systems rely heavily on satellite timing, and that dependence has become a growing vulnerability. GPS signals can be jammed, spoofed, or disrupted by natural phenomena such as solar storms. Critical infrastructure—from aviation to power distribution—depends on synchronized timing, yet today’s atomic clocks drift too quickly for long-term, standalone use. This gap has led researchers to search for ultra-stable alternatives that can maintain accuracy even when satellite signals disappear.

According to Interesting Engineering, a new development in thorium-based nuclear clocks may pave the way forward. A UCLA-led team has demonstrated a simplified manufacturing method that replaces years of complex crystal engineering with a much more accessible industrial process: electroplating. The breakthrough builds on recent work showing that thorium-229 nuclei can be driven to absorb and emit energy in a controlled manner, a foundational requirement for building a nuclear clock.

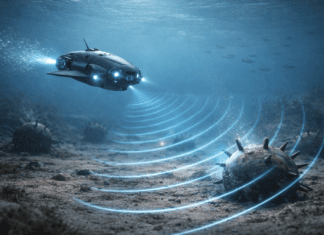

A compact, drift-resistant clock could enable precision navigation for submarines, autonomous systems, and long-range platforms operating where GPS cannot be trusted. It could also provide resilient timing for communications, radar networks, and other mission-critical systems that must function during electronic warfare or large-scale outages.

The original approach to thorium clocks relied on growing specialized transparent crystals that held relatively large amounts of thorium—an isotope that is extremely scarce, with only around 40 grams available globally. The new method sidesteps that barrier by electroplating a microscopic layer of thorium onto stainless steel, reducing material use by roughly a factor of 1,000. Researchers found that only nuclei near the surface need to be excited, and that their response can be measured through emitted electrons rather than emitted light. This discovery eliminated the need for fragile transparent hosts and made the clock medium far more durable.

Because the electroplated layer behaves consistently under laser excitation, the team was able to detect the nuclear response simply by monitoring electrical current from the surface. The technique opens the door to robust, manufacturable devices rather than laboratory-grade prototypes.

As research progresses, scientists say the approach could lead to smaller, more stable nuclear clocks suitable for field deployment—potentially reshaping navigation, communications timing, and even deep-space mission planning.

The research was published here.