This post is also available in:

עברית (Hebrew)

עברית (Hebrew)

Building an aircraft that can fly several times faster than sound has always been one of aviation’s hardest engineering challenges. At hypersonic speeds, temperatures soar, materials weaken, and traditional jet engines stop functioning altogether. For decades, the idea of a practical hypersonic aircraft remained beyond reach. However, a new generation of hydrogen-powered scramjet systems is now pushing that boundary much closer.

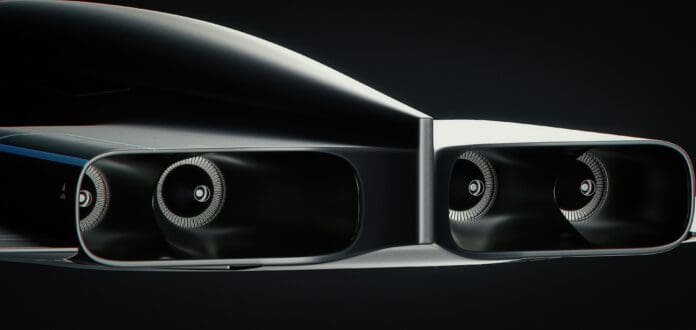

The core problem in hypersonic propulsion is sustaining combustion while air races through an engine faster than the speed of sound. Scramjets solve this by compressing the incoming airflow through sheer velocity alone, eliminating the need for rotating compressor parts. But they require extremely high energy density to maintain stable combustion—something conventional fuels struggle to deliver. Hydrogen’s high specific energy and clean combustion profile make it one of the few fuels capable of keeping a scramjet lit at extreme speed.

According to Interesting Engineering, recent tests demonstrate how this combination could power long-duration hypersonic platforms. Demonstrator vehicles built with fully 3D-printed high-temperature alloy engines are made to operate between Mach 5 and Mach 12, a speed range relevant for future reconnaissance aircraft, rapid-response strike systems, and even small-satellite launch vehicles. Operating at these velocities means surviving temperatures that exceed 1,800°C, requiring advanced ceramic matrix composites and lightweight thermal structures capable of holding their shape under intense aerodynamic loads.

Because scramjets cannot operate from a standstill, hypersonic aircraft need hybrid propulsion—typically a booster stage to accelerate the vehicle to scramjet ignition speed. Once active, the scramjet becomes more efficient the faster it travels, opening the door to long-range, high-speed flight using only atmospheric oxygen and hydrogen fuel.

For defense planners, hypersonic propulsion offers clear advantages. High-speed reconnaissance vehicles could enter contested airspace, collect intelligence, and exit before detection. Hypersonic strike platforms could deliver payloads with shorter reaction times, while reusable demonstrators would allow rapid testing of new materials and guidance systems.

Commercial aviation may eventually benefit as well, but passenger hypersonic travel remains far off. The technical hurdles—thermal protection, emergency protocols, and cryogenic hydrogen handling—are far more demanding than those for unmanned vehicles.

Still, progress in hydrogen scramjets signals that practical hypersonic flight is no longer a distant concept. As materials, manufacturing, and fuel systems continue to improve, the next era of aviation may be defined not by breaking the sound barrier, but by multiplying it.