This post is also available in:

עברית (Hebrew)

עברית (Hebrew)

For decades, engineers have relied on a simple rule when designing stronger metals: make the grains smaller, and the material becomes harder and more resistant to damage. This principle, known as the Hall–Petch relationship, has shaped everything from aircraft structures to protective armor. But new research suggests that under extreme conditions, that rule no longer applies—and may even work in reverse.

Researchers studying how metals behave at very high deformation speeds have found that when materials are struck at supersonic velocities, reducing grain size can actually make them softer rather than stronger. The discovery emerged from experiments designed to test the limits of long-established materials science assumptions, particularly in scenarios involving ultra-fast impacts.

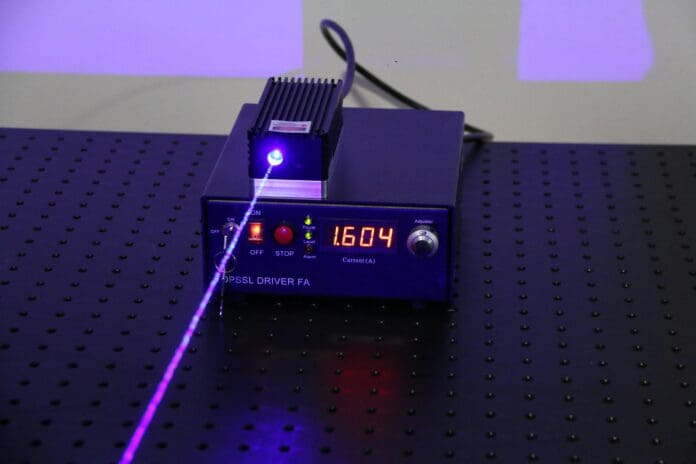

To probe this regime, the team used laser-driven microprojectile impact testing. In these experiments, microscopic particles are fired at metal samples at speeds exceeding the speed of sound, generating deformation rates far beyond those seen in conventional mechanical tests. This approach allowed researchers to observe material behavior under conditions similar to ballistic impacts or high-velocity debris strikes.

According to Interesting Engineering, copper samples with grain sizes ranging from one to 100 micrometers were tested. Under normal loading rates, smaller grains behaved as expected, resisting deformation. At supersonic impact speeds, however, the opposite occurred. Samples with larger grains showed shallower impact craters and dissipated more energy, indicating greater resistance to damage. Repeated tests confirmed the trend, ruling out experimental error.

The explanation lies in how metals deform at extreme speeds. Under typical conditions, grain boundaries block the movement of dislocations—microscopic defects that enable metals to deform—thereby strengthening the material. At ultra-high strain rates, dislocations move so rapidly that they begin interacting strongly with atomic vibrations in the crystal lattice. This phenomenon, known as dislocation–phonon drag, adds resistance to motion and changes the dominant strengthening mechanism. In this regime, fewer grain boundaries can actually be beneficial.

Although the experiments focused on copper, early tests on other metals and alloys suggest the effect may be widespread. If confirmed, this insight could prompt a rethink of how materials are optimized for extreme environments.

From a defense and security perspective, the implications are significant; armor systems, protective vehicle structures, and munitions all experience high-strain-rate impacts. Designing materials specifically for these conditions—rather than relying on assumptions valid at lower speeds—could improve protection while reducing weight. Similar considerations apply to spacecraft, where shielding must survive collisions with high-speed debris.

Beyond defense, the findings may influence additive manufacturing, where grain size can be carefully controlled, and any application involving impacts or shock loading. More broadly, the research highlights how materials that behave predictably under everyday conditions can reveal unexpected properties when pushed to their limits—opening new paths for engineering in extreme domains.

The research was published in the Physical Review Letters journal.