This post is also available in:

עברית (Hebrew)

עברית (Hebrew)

Controlling large numbers of attack drones has become one of the biggest challenges in modern warfare. Individually piloted systems already strain operators, while electronic warfare and time pressure make precise coordination even harder. As drone numbers increase, the traditional one-operator–one-drone model simply does not scale.

A recent live-fire demonstration points to a different solution. In the test, a single operator successfully struck three separate targets at the same time using three small attack drones. Rather than manually flying each drone, the operator selected targets on a screen and then delegated execution to onboard software. From that point on, the drones coordinated the attack autonomously.

The key enabler is swarm-control software (Auterion’s Nemyx swarm software) that shifts the human role from pilot to mission commander. Once airborne, each drone runs the same swarm engine locally. The system distributes tasks, assigns priorities, and manages timing without continuous human input. The drones exchange information about position, status, and target allocation, allowing them to adapt as a group rather than as isolated platforms.

According to Interesting Engineering, if one drone fails or is lost, the others automatically reorganize. Another drone can take over the abandoned target without external commands. The software is also designed to operate in contested electromagnetic environments. Even if communications are disrupted entirely, each drone continues toward its assigned objective using its own onboard logic.

Safety and control are built into the design. A certified safety layer allows commanders to arm or disarm the entire swarm instantly, ensuring that lethal force remains under human authority. This predictability is critical for military adoption, where reliability and controllability are as important as effectiveness.

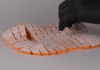

Notably, the demonstration emphasized software over hardware. The drones used were relatively simple quadcopters similar in size and performance to widely available first-person-view systems. Their individual capabilities are modest, but when combined into a coordinated swarm, their impact increases significantly. The same software can be applied to other drone types, including larger quadcopters, fixed-wing systems, or longer-range strike platforms.

Swarm-enabled drones allow a small number of operators to generate effects that previously required much larger teams. They could be used to suppress air defenses, strike multiple vehicles simultaneously, or overwhelm targets through coordinated timing rather than sheer firepower. For border security or force protection, swarms also offer rapid response against multiple threats appearing at once.

The test suggests that drone warfare is moving beyond incremental improvements. Coordinated swarms represent a qualitative shift, where software intelligence—not airframe performance—becomes the decisive factor in how unmanned systems are employed on future battlefields.