This post is also available in:

עברית (Hebrew)

עברית (Hebrew)

As indoor lighting shifts almost entirely to LEDs over the next decade, researchers are examining whether these lamps can play a much larger role than illumination alone. A growing body of work suggests that the same light sources used in homes, hospitals, aircraft cabins, and factories could function as communication tools and even as power sources for small devices, turning everyday lighting infrastructure into a dual-use platform for connectivity and energy harvesting.

Conventional wireless networks rely on radio signals, which are efficient but can be problematic in sensitive environments. Hospitals, manufacturing floors, and aircraft all restrict certain radio emissions due to the risk of interference with critical systems. The challenge is how to provide reliable digital communication without exposing equipment or personnel to unnecessary radio activity.

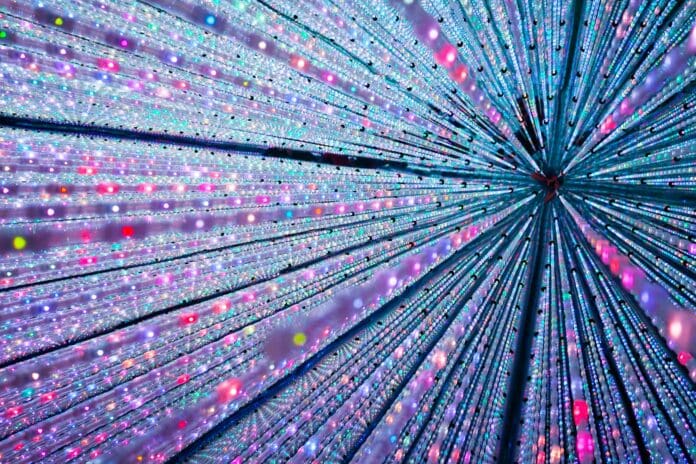

Researchers at the University of Oulu are advancing a potential solution through visible light communication (VLC), which is a technique that transmits data using rapid, imperceptible flickers of LED light. Because LEDs can be switched on and off at high speed, they can encode the ones and zeros of a digital signal much like Morse code. A receiving device interprets the changes in brightness, while the user sees only a steady beam. The reverse link, from phone to lamp, can rely on infrared light to avoid visible flashes.

According to TechXplore, since light cannot pass through walls, VLC offers a built-in security advantage: data remains confined to the room where the light source is located. For defense, aviation, and medical environments where electromagnetic control is crucial, light-based communication could provide a controlled and interference-free channel that complements existing radio systems rather than replacing them.

The research extends beyond data transmission. The team is also exploring how small IoT devices could power themselves using the same LEDs that support communication. Using miniature solar cells, low-power sensors could harvest energy from ambient light and operate without batteries. Combined with printed electronics, this approach could enable disposable or sticker-like monitoring tags that track conditions such as temperature, humidity, or equipment location.

In their broader vision, future devices may shift seamlessly between radio and light depending on environmental constraints. With LEDs projected to dominate indoor lighting worldwide by 2035, turning this ubiquitous infrastructure into a communication and power network could offer both sustainability gains and safer connectivity in sensitive operational settings.