This post is also available in:

עברית (Hebrew)

עברית (Hebrew)

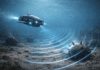

Three-quarters of pedestrian deaths in the US happen at night, according to federal data. Night driving poses the same challenges for autonomous cars that it does for human drivers. The darkness shrouds objects and people because there’s not enough contrast to observe the scene clearly. That is particularly vexing for cameras – one of three key sensors, along with radar and lidar – that allow autonomous cars to “see” their surroundings. At night, cameras’ field of vision is limited by headlights that project only about 80 meters ahead, giving drivers-robots or humans-only a couple of seconds to react.

A few weeks after a woman was struck and killed by an Uber self-driving SUV in Arizona, the crash was recreated using heat-seeking thermal-imaging sensors. With that night vision technology – used by the military and luxury cars for decades – the pedestrian is clearly identified more than five seconds before impact, which would have given the car time to stop or swerve.

Autonomous car researchers have been looking for ways to teach robots how to drive in the dark and avoid people who wander into the road. One fairly obvious solution has been in some cars for almost 20 years: night vision that can detect the heat of a human body.

Companies such as Seek Thermal, which recreated the Uber crash, and headlight makers such as Osram have been pushing thermal and infrared sensors as the missing link in autonomous driving, according to thestar.com. And since the Uber crash – where a woman walking her bicycle wasn’t recognised as a pedestrian in time to avoid a collision – the creators of robot rides are starting to take notice.

Night vision can more than double an autonomous vehicle’s range of vision at night, according to advocates for the technology, but it has a reputation for being costly, with thermal sensing units going for $5,000 each. That’s a reason auto and tech companies creating robot rides are taking a pass on the tech.

Lidar and radar are impervious to the dark because they bounce laser light and radio waves off objects to assess shape, size and location. But they can’t detect heat to determine if those objects are living things. That’s why pedestrian detection could remain a challenge for self-driving cars.

“For lidar, the question is, ‘Is it a fire hydrant or is it a 4-year-old?’” said Tim LeBeau, vice president of Seek Thermal, who’s trying to get automakers to buy his company’s infrared sensors that are now used by law enforcement, firefighters and hunters. “With fire hydrants, you can predict what’s going to happen. Four-year-olds, you cannot.”

Part of LeBeau’s pitch is that the cost of thermal sensors is dropping about 20% a year as they become more widely used. The National Transportation Safety Board’s report on the Uber crash also provided more fodder. The agency’s preliminary findings bolstered the case for using redundant sensors that can better differentiate between inanimate objects and human beings, he said.

Advocates of the technology are hoping automakers can see night vision as more than a tech toy for moneyed motorists to recognise stags bounding onto a gloomy roadway. They contend it’s an essential element of machine vision, enabling self-driving cars to brake and steer in the dark better than any human driver.