This post is also available in:

עברית (Hebrew)

עברית (Hebrew)

![]() By Christian de Cock

By Christian de Cock

INSS – Military and Strategic Affairs Program

A War is a War is a War?

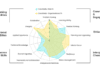

Although at first sight many issues related to targeting densely populated areas seem similar, regardless of the type of conflict and the area where hostilities take place, it should be recalled that what works in the framework of one operation does not necessarily work in another operational context.1 This can be illustrated by two contemporary conflicts in which air assets play or played a major role: Afghanistan and Libya. Air operations conducted in the framework of International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) are similar but not identical (and thus different) from those conducted during Operation Unified Protector (OUP). This is based on the fact that different criteria impact on the execution of air operations, including: the strategic end state, the nature of the enemy forces, the classification of the conflict, the mission-specific air operations, the presence of ground forces, and the rules of engagement (table 1). It is crucial to be aware of those differences, because otherwise there is a risk of applying the wrong standards or the wrong rules of engagement to the wrong conflict. What worked for Operation Unified Protector worked in Libya (at that time) but doesn’t necessarily work in Afghanistan, and vice versa. This is a logical consequence of the differing surrounding conditions in which the air crews had to operate in Afghanistan and Libya. In sum: every conflict is characterized by its own dynamics, despite the similarities to other conflicts.

Although at first sight many issues related to targeting densely populated areas seem similar, regardless of the type of conflict and the area where hostilities take place, it should be recalled that what works in the framework of one operation does not necessarily work in another operational context.1 This can be illustrated by two contemporary conflicts in which air assets play or played a major role: Afghanistan and Libya. Air operations conducted in the framework of International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) are similar but not identical (and thus different) from those conducted during Operation Unified Protector (OUP). This is based on the fact that different criteria impact on the execution of air operations, including: the strategic end state, the nature of the enemy forces, the classification of the conflict, the mission-specific air operations, the presence of ground forces, and the rules of engagement (table 1). It is crucial to be aware of those differences, because otherwise there is a risk of applying the wrong standards or the wrong rules of engagement to the wrong conflict. What worked for Operation Unified Protector worked in Libya (at that time) but doesn’t necessarily work in Afghanistan, and vice versa. This is a logical consequence of the differing surrounding conditions in which the air crews had to operate in Afghanistan and Libya. In sum: every conflict is characterized by its own dynamics, despite the similarities to other conflicts.

End State

First of all, the strategic objectives in Afghanistan and Libya were different. While in Afghanistan the strategic objective was/is to create “a secure and stable environment,” in the Libyan Unified Protector mission the strategic objective was “to protect the civilians and civilian populated areas under attack or threat of attack” by the Libyan armed forces and associated forces. It is important not to lose sight of these strategic objectives, as the importance of strategic objectives is not purely academic. Strategic objectives are important because even in situations where the use of force is authorized by implemented rules of engagement (ROE), the tactical advantage to be gained from an attack can have tremendous consequences on the strategic level. Those strategic objectives are translated into a military end state where decisive points will be defined in the operational planning process. But in order to achieve those decisive points, e.g., gaining and maintaining air superiority, accurate rules of engagement are needed to allow the armed forces to conduct the operation in accordance with the mandate and to achieve, at the end of the armed conflict, the strategic objectives established by the UN Security Council resolutions.

Boots on the Ground

The operations in Libya and Afghanistan were also different in terms of the type of war that was waged, the nature of the enemy, and the capacity of the NATO forces that were engaged. In Afghanistan ground forces were available so an aircraft could be guided to a military objective by qualified forward air controllers. For example, the Joint Terminal Attack Controller (JTAC) could help lead that aircraft to the military objective and strike that military objective. That was not the case as far as the operations in Libya were concerned. NATO had no boots on the ground. Consequently, aircrew could not rely on JTAC to positively identify ground targets and the assessment of the ground commanders with regard to the combat development (CD) to be expected from the attack. Other means were used to make such determinations, and experience proved that these processes met the standards to comply with the requirements of the law of armed conflict.

Irregular Warfare Used by a Non-State Actor

Another difference between the two operations is that the ISAF in Afghanistan is fighting an asymmetric war against a non-state actor (NSA) that deliberately refuses to comply with the laws of armed conflict. This made ISAF a counterinsurgency operation, and this meant that the means and methods of combating those non-state actors had to be adapted significantly to achieve the final objective. Today, the conflict in Afghanistan can be classified as a non-international armed conflict (NIAC).

In Operation Unified Protector, at least when NATO operations began, the conflict pitted the Libyan armed forces against the coalition forces. According to the traditional principles of warfare, this was an interstate armed conflict between two or more states. Later, however, the Libyan armed forces changed their tactics and their strategy from traditional warfare to irregular warfare. They stopped wearing uniforms and began using vehicles that were difficult to distinguish from civilian vehicles. This made it much more difficult for NATO to distinguish between the armed forces, mercenaries, and other individuals’ affiliated with Libyan armed forces and the civilian population. This of course did not alter the classification of the conflict, which was still international in character. The point is that even in the context of an international armed conflict, NATO and NATO-led forces were confronted with irregular warfare from regular forces, and consequently, the approach that had to respond to this new phenomenon was somewhat similar to the tactics and procedures used in traditional counterinsurgency campaigns. When regime forces were forced to flee and the Transitional National Council took power after the fall of Tripoli, the conflict between NATO/NATO-led forces and the former regime troops became a non-international armed conflict.

This was also the case in Afghanistan. When Karzai took office in Kabul, the conflict in Afghanistan shifted from an international armed conflict (IAC) to a non-international armed conflict. In Libya, from a targeting perspective, this change in government made no difference as far as dynamic or deliberate targeting issues were concerned. Coalition forces continued to apply the standards of the law of international conflict, even though from a legal point of view, the situation evolved from an IAC to an NIAC. In other words, there was no legal consequence of this change, since coalition forces continued to apply the rules of international conflict in the context of a non-international armed conflict. The legal framework for the intervention was based on the law of international armed conflict, which is basically customary international law, the Geneva Conventions, and the Additional Protocol I (AP I).

Impact of Air Missions

The air missions in Libya were also quite different from the missions that were carried out in Afghanistan, influenced by, inter alia: the objectives of the operations, the availability of ground forces to assist aircrew in their missions, and the type of targets to be pursued. In most cases, the air missions in Afghanistan can be classified as “close air support” missions in order to support the ground forces. In Libya, air operations ranged from defensive counter air to offensive counter air missions. From a targeting point of view, ISAF air missions were flown more “dynamically,” while Operation Unified Protector combined “deliberate” and “dynamic” missions. In the beginning, the focus was rather “deliberate” and shifted later to more “dynamic” missions. Additionally, the deliberate targeting process had to be shortened in order to keep on track with the operational pace.

The operation had three main objectives. The first goal was the protection of civilians and civilian populated areas under attack or threat of attack, which was to be accomplished without a foreign occupation force. The second objective was to enforce the no-fly zone. There was not necessarily a direct link between the enforcement of the no-fly zone and the protection of the civilian population. In practice, it was not always clear whether a particular engagement was part of the second objective, the no-fly zone, or whether it was part of the first objective, the imperative to protect civilians and civilian populated areas. The third objective was the embargo.

Regarding the OUP strategic objective of protection of the civilian population and civilian populated areas under attack or threat of attack, one of the issues that arose was whether or not the objective was limited to jus ad bellum. Was it necessary to have a direct and causal link between the military objectives planned by NATO and the strategic objective of protecting the civilian population? In other words, each time the crew decided to strike a particular target did they need a direct link to the protection of the civilian population, or was this strictly the overall strategic objective and the end state? Different views exist on the interpretation of this wording in the UNSC Resolution. The protection of the population as a strategic end state permitted the striking of targets, even if they were not directly attacking the civilian population. Other issues arose from the wording of UN Security Council Resolution 1973.

It is important to note that NATO did not support the rebels against the forces of Colonel Qaddafi. The mandate was clear in this respect. NATO and the coalition of the willing (before NATO assumed responsibility for the implementation of UNSCR 1973) were engaged to protect the civilians and the civilian population. Although some indirect effects of this intervention did benefit the rebels in their internal armed conflict against the regime forces, there was no deliberate support for the rebels in their fight against the regime forces. Consequently, the conflict in Libya was not an “internationalized” internal armed conflict. From a legal point of view, there were two armed conflicts on Libyan territory: a non-international armed conflict between the rebels and the regime forces, and following the implementation of UNSC Resolution 1973, an international armed conflict between NATO-led countries and the Libyan armed forces. There was a coexistence of two different armed conflicts, and the NATO nations did not consider themselves involved in an internationalized non-international armed conflict. This also results from the wording of the mandate, which did not mention the opposing parties in the respective operative paragraphs of the resolution. The mandate had to be implemented in an impartial way and the Security Council resolution was construed broadly, so that if the rebels attacked civilians or civilian populated areas, NATO could engage rebel forces as well. The second aspect that confirms that NATO did not support the rebels is the fact that NATO gave Qaddafi forces the opportunity to retreat and return to their barracks. Had they taken this opportunity and had rebel forces attacked them, then the regime forces would have had an inherent right to defend themselves and the coalition would not have interfered in this internal struggle.

In conclusion, there were two different parties, the rebels and the regime forces, regulated by the law of non-international conflict. Until the fall of Colonel Qaddafi’s regime, there was an international conflict between the different nations of the coalition and the regime forces of Colonel Qaddafi. Later, the IAC turned into an NIAC when the National Transitional Council became the governing authority in Tripoli.

Direct Participation in Hostilities

Mercenaries who on an individual or organized basis assisted the Libyan authorities in suppressing civilians, mainly in the eastern part of Libya, were considered to be directly participating in hostilities. From an international humanitarian law (IHL) perspective, if an individual is a member of an organized armed group, and if he/she participates in hostilities, then he/ she becomes a legitimate military target. Organized armed groups acting as armed forces of non-state actors are legitimate military objectives for the entire duration of the conflict, unless they leave the group or become hors de combat.

Some human rights advocates argue that these individuals can only be targeted if they have a “continuous combat function,” as suggested by the ICRC Interpretive Guidance on the notion of direct participation in hostilities. This is false. If these individuals are members of an organized armed group, they are a legitimate military target on a 24/7 basis for the entire duration of the conflict, whether they perform a combat, combat support, or even combat service support function (unless they become hors de combat). This principle also determined the way in which mercenaries and other persons who directly participated in hostilities, without being a member of the Qaddafi armed forces, were considered in terms of targeting. They were considered legitimate military targets. Furthermore, individuals or groups who were not directly attacking the civilian population at a certain point but were known to be a future threat to civilians could also be targeted without violating international humanitarian law.

.

Voluntary Human Shields

Civilians who give up their immunity to deliberately and voluntarily shield military objectives from attack are directly participating in hostilities, and while they participate directly in hostilities they lose their immunity from attack. The military objective they are trying to protect can be attacked, and the voluntary human shield should not be factored into the proportionality analysis.

Three basic views exist on this particular issue. IHL advocates argue that even voluntary human shields remain civilians, and consequently they may not be attacked and should be accounted for in the proportionality analysis. At the other end of the spectrum, some argue that those who engage in voluntary shielding are directly participating in hostilities and thus are liable to attack. Finally, the middle position is that they are not directly participating in hostilities, but on the other hand, should not figure in the proportionality analysis.

Human Rights Law and Targeting

The role of human rights in the law of armed conflict is controversial. Proponents of human rights have tried to introduce principles such as the right to life within the context of the law of armed conflict (LOAC) for the purpose of targeting and the use of force.

Human rights law cannot be applied in the targeting process. In the conduct of hostilities in international armed conflict, the lex specialis is the law of armed conflict, which unambiguously determines who can and cannot be targeted. If the enemy combatant (the term is used here in a generic way) is not hors de combat, he/she remains a legitimate target on a 24/7 basis for the entire duration of the armed conflict. There is no place for human rights in the conduct of hostilities with regard to the principle of distinction or the principle of proportionality.

The proportionality analysis under human rights law is totally different from proportionality in the law of armed conflict, as enshrined in the AP I. The proportionality analysis in human rights law is a strict proportionality analysis in the framework of the right to life provision, which can be found in the different regional human rights conventions such as the European Convention on Human Rights. The European Court of Human Rights should embrace its essential mission, which is the safeguarding of human rights in a human rights context. In a situation of peace or an emergency situation, the right to life provision applies, and a court must apply this provision. But if the court is dealing with an international human rights issue in the context of an armed conflict, then there is no place even under Article 2 for the right to life provision, which distorts LOAC to the point that it makes no sense.

.

Targeting Process

Once the war began, the key missions for coalition air forces were essentially to enforce the no-fly zone in order to gain and maintain air superiority, prevent (artillery and armored) attacks on civilian areas, and enable humanitarian assistance missions to enter Libya. NATO-led air forces had an unprecedented ability to execute these missions and the ability to paralyze the Libyan air force. The systematic suppression of Libyan air defense systems allowed NATO to achieve air superiority shortly after the first days of the operation.

The ability to rapidly target and re-target proved to be crucial in achieving the mission objectives, especially when regime forces transformed their fighting tactics from regular to irregular warfare. One of the major concerns was that the 72-hours deliberate targeting process could not (always) keep pace with the dynamics of the battlefield, because the planning to execution cycle was too long and the process did not react quickly enough to changes in the scheme of maneuver. Shortening the 72-hours targeting cycle and pushing the targeting planning cycle closer to execution helped keep the Prioritized Target List more current (and relevant) during Air Task Order execution. A guiding principle of the air campaign was to achieve maximum effect with minimum force. The use of precision guided munitions was the key, helping NATO achieve its objectives more quickly while minimizing

civilian casualties. Precision weapons were used against targets in (densely) populated areas where the aim was to destroy single targets while leaving neighboring buildings intact. Because no ground troops were deployed during OUP, unmanned aerial vehicles (UAV) were of utmost importance.

One of the central lessons learned during OUP was that the mandate should be very clear so that operators do not have any doubt as to what they can and can’t do in the context of an armed conflict. It is the responsibility of the legal advisors to assist the operational staff in interpreting and translating those rules of engagement so they can be applied in day-to-day operations. Pilots must receive clear instructions as to what they can do and can’t do in prosecuting targets. In dynamic targeting in Libya, the targets were categorized according to the level of civilian or collateral damage that resulted from the strike. The higher the expected collateral damage, the higher the authority needed to engage that target. In order to protect pilots against prosecution for their actions during such an operation, the pilots’ decision making authority was restricted to basic levels of lower collateral damage levels, with no nearby collateral damage concerns within the range of their ordinance (type GBU 12 and 38). All other targeting decisions, that is to say exceeding the collateral damage levels delegated to the aircrew, had to be dealt with within the Combined Air Operations Center (CAOC), which is essentially what was done during Operation Unified Protector as well. In dynamic and in deliberate targeting, if the level of collateral damage exceeded the aircrew-delegated CD authority levels, the decision to strike was transferred to the Combined Air Operations Center (CAOC) for further consideration. This is because at the CAOC, additional intelligence was available that could be used to assess the collateral damage concerns, such as, inter alia, live feed from UAVs (if and when available). The live feed was sometimes used to assess whether the targeting and prosecuting of a particular target still complied with the LOAC requirements. Intelligence and UAVs proved to be crucial, especially where C2 nodes and other targets were located in urban areas.

Conclusion

Operation Unified Protector was conducted successfully by NATO and NATO-led forces in order to achieve the strategic objectives in accordance with the UNSC mandate. Different issues arose in the context of this operation, both legally and operationally. From a legal perspective, the conflict was an international armed conflict until the National Transitional Council took power following the fall of Tripoli. Despite some ambiguities in the wording of the mandate, NATO succeeded in conducting air operations and protecting civilians and civilian populated areas under attack or threat of attack.

The presence of mercenary activities raised some questions on the issue of direct participation in the hostilities. Civilians affiliated with the regime forces involved in attacking and threatening to attack the civilian population are directly participating in the hostilities and are liable to attack during the entire conflict, unless they become hors de combat. Although the issue of voluntary human shields did not arise during OUP, there were some discussions on the use of involuntary human shields by the regime, in which case they could not be attacked. Even assuming that the incidental damage in attacking the military objective they were shielding was not excessive in relation to the military advantage to be gained from the attack, it would have been illogical and contrary to the perceived end state (and mandate) to do so, since NATO’s mission was the protection of civilians. The main focus of the operation was to prevent the attacks and the threat of attacks on civilians.

OUP has undoubtedly been the most intense NATO air campaign since Operation Allied Force during the Kosovo conflict in 1999. It has proved that air assets are critical parts of every modern operation and can contribute to the success of a military campaign. In all phases of OUP, constant care was taken to comply strictly with the Security Council mandate and the imperatives of the law of armed conflict. When requirements changed and pro-Qaddafi forces shifted their tactics from regular to irregular warfare, NATO-led forces proved to be capable of responding rapidly and adequately to these changing circumstances. The use of precision guided weapons, coupled with hi-tech intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) assets, was crucial to the fulfillment of the mission. Using precision laser-guided and satellite-guided munitions made every strike count. With a minimum of collateral damage, the air strikes enabled NATO to enforce the mandate. Operation Unified Protector offered convincing proof that airpower is flexible enough to take the lead in many different types of conflict. In targeting enemy forces, NATO forces strictly adhered to their obligations under the law of armed conflict. Targets were positively identified prior to prosecution, and all feasible precautions were taken in order to minimize the damage to civilian property and the civilian population..

Lieutenant Colonel (GS) Christian de Cock is Chief of the International Law Section at NATO. He served as a legal advisor assisting BEL air crews in NATO missions in both Afghanistan and Libya.

Lieutenant Colonel (GS) Christian de Cock is Chief of the International Law Section at NATO. He served as a legal advisor assisting BEL air crews in NATO missions in both Afghanistan and Libya.

This article was first published in Military & Strategic Affairs journal. Volume 4, issue 2.

To read the full article, press here (link):

Operation Unified Protector Targeting Densely Populated Areas in Libya-Christian de Cock